Monday, February 29, 2016

Inside the C.G. Conn factory ca. 1911

I couldn't let this leap year day pass me by without posting something. So click here for a great set of photographs that I stumbled upon that provides an inside look at the C. G. Conn factory around 1911. At the end is a brief history of Conn and his company, although the passing remarks about the first Sousaphone perpetuate the wrong understanding that Conn was responsible for it. But they were cranking out some fantastic horns at that time!

Sunday, February 21, 2016

So then it's really a Sue-sar-phone?!

Among the gems that I found while at the U. S. Marine Band Library (just over a year ago) that were not directly related to Sousaphone history was this explanation of how to pronounce Sousa's name - written by Sousa himself:

This was in Sousa Band Press Book no. 8, and is a clipping from the April 23, 1899 edition of the New York Journal. Here's the accompanying article:

I'm not entirely sure what the "good old-fashioned way" of pronouncing it was back then, but today we tend to say "Sue-zuh," and "Sue-zuh-phone." But I guess it should be "Sue-sar" and "Sue-sar-phone"!

This was in Sousa Band Press Book no. 8, and is a clipping from the April 23, 1899 edition of the New York Journal. Here's the accompanying article:

I'm not entirely sure what the "good old-fashioned way" of pronouncing it was back then, but today we tend to say "Sue-zuh," and "Sue-zuh-phone." But I guess it should be "Sue-sar" and "Sue-sar-phone"!

Saturday, February 20, 2016

At the U. S. Marine Band Library

And while I should have posted on this back when I made the trip in December 2014, I thought I'd finally record it and share what I found while I was there.

To begin with, the historical significance of the area, and its resident band, is apparent from the street as you approach the Marine Barracks. Here is the sign that is posted along the walkway, about a block away:

And here's a close-up of the text, if you're interested in the history of the band, as well as its most famous leader:

I had driven down to D.C. from Philadelphia on Sunday night, December 28th, in order to spend all day Monday, the 29th, in the Library. Welcoming me warmly was Gunnery Sergeant and Assistant Chief Librarian and Historian of the U. S. Marine Band, Kira Wharton (who was not required to be in uniform that day):

Kira graciously gave me the grand tour of the Library, and pulled all of the relevant documents for me to look at, which included copies of the Sousa Band Press Books (the originals are locked away in fire-proof cabinets), as well as the Library's files on the history of the Sousaphone. She set me up with a great workspace (below), and even helped by doing some online newspaper searches for the earliest references to the Sousaphone (the Marine Band was on break, so she offered to assist me, which was wonderfully kind!).

So what did I find, over the course of the day, as it relates to the history of the Sousaphone? Well, the most important thing is what I didn't find.

As it turns out, while the Sousa Band Press Books are a fantastic resource - a kind of scrap book of news-clippings on Sousa's band over the course of it's 40 year history - there is a gaping hole in the series. Book no. 3 ends with September 3, 1894, and book no. 4 begins with June 14, 1896! That gap is the very period in which the first Sousaphone was built by J. W. Pepper and went on tour with the Sousa Band! I was totally bummed!

What happened to the news-clippings from that period? Were they lost at some point, or were they perhaps not kept for those months? We simply do not know at present.

But all was not lost for my day at the Library. I did find a number of important references to Conn's first Sousaphone, which was introduced in January 1898 (probably having been built in late 1897, although Conn has only ever mentioned 1898 as its birth year).

It was Kira who found the most historically significant reference in the course of her online newspaper searches. Notice what it says on page 7 of the January 17, 1898 edition of The Washington Post:

This is now the earliest known reference to a Sousaphone in the press (apart from a few J. W. Pepper publications in 1895 and 1896). It almost certainly is speaking of Conn's new horn, which was more formally introduced five days later, on page 11 of the January 22, 1898 edition of The Music Trade Review (which I found in Press Book no. 5, although I had seen it before):

While this notice seems to speak of the Sousaphone as if no one would have seen one yet, the Washington Post reference above, from a week earlier, suggests the new instrument was already known by that time (perhaps from the Pepper Sousaphone travelling with the band in 1896?).

The next reference I found in the Press Books was from a month or so later (February 1898, although this is just a guess, based on where it appears in Book 5). The Sousaphone is mentioned in a poem by F. W. Wadsworth, which is part of a larger article titled "Sousa and His Band: Matchless Organization Plays to an Immense Enthusiastic Audience." (unfortunately, neither the newspaper nor the date accompanies the clipping). Here's the entire, rather cheesy, poem for your reading pleasure!

Did you catch the reference?

In this fundamental trio [of basses],

Noted for volume and depth of tone,

There's one of tremendous size,

Known as the "Sousa-Phone."

The extra attention given to the "Sousa-Phone," as well as the hyphen in the name, suggests that the instrument was a recent addition. But notice also the reference to "volume and depth of tone." This was what Sousa was searching for in creating the Sousaphone in the first place - a big, warm sound that would pour over the band from the huge, upright bell.

In Press Books 8 and 9 we get our first look at a "Sousa-Phone" - a drawing from the September 17, 1899 edition of the Pittsburgh Post. The extensive article, written by Gustave Schlotterbeck, was titled, "March Master and His Method," and featured this:

The horn matches one made by Conn, but interestingly, it is not the first model of Sousaphone that Conn built (the valve cluster changed at least two times before Conn was satisfied; for more on this, click here).

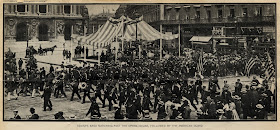

Here's one last find from my day at the Library. In Press Book 12, I came across an actual photograph of the Sousaphone in use in Sousa's Band - and on parade at that (something Sousa rarely did). It was in the August 4, 1900 edition of Collier's Weekly, which featured the band in Paris. This was not a photo I had seen before, so Kira pulled the original so that she could get a quality scan of it for the Library. Check out what can be seen on the far left of the front rank, as you are looking at the photo:

I'll zoom in so that you can see the big horns up front - a Sousaphone and three tubas:

This wasn't the first time a Sousaphone was seen on the march (that happened back in the States), but it may very well have been the first time for such a spectacle in Europe.

Of course, I found many other interesting things in the Press Books, but these are the most relevant to the early history of the Sousaphone.

In wrapping up this long post, let me take you outside of the building, where stands the one and only statue of the namesake of that great bass horn:

Sunday, February 14, 2016

Friday, February 12, 2016

A Selective History of J. W. Pepper

1853

- James Welsh Pepper was born in Philadelphia to William (1819-1882) and Rachel (Pippett, 1821-1894) Pepper on March 8.

- His parents founded a printing business in 1845 in south Philadelphia, where James apprenticed, and eventually worked as an engraver.

- He grew up at 1508 N. 13th Street, Philadelphia (not sure which year his parents settled there, but James remained there until he was 25, in 1878).

- James had an older sister, Clara (1847-1927) and older brother, Charles Howard (1848 or 49-1880).

1860

- Carolene Clementine Nicholls, the woman James would eventually marry around 1879, was born in Delaware in June.

- “Commenced business in a small way, in 1876 (Centennial Year) at 9th and Filbert Streets as a publisher of band, orchestra and miscellaneous music” (Source: Pepper's 1897 Catalogue).

- The address was 832 Filbert Street. There are no known images of the building.

- However, records show that, for at least part of this year, James worked out of 702 Chestnut Street.

- John Philip Sousa moved to Philadelphia that year and was based in that city for the next four years. Sousa was 21 when he made the move. Pepper was probably 23.

- The company was definitely based at 832 Filbert Street by this year - and until 1881. James was listed as an "engraver."

- Publication of J. W. Pepper's Band Journal began (in 1881 or 1882 it was renamed J. W. Pepper's Musical Times and Band Journal).

1879

- On July 20, Pepper published the first of eleven marches by John Philip Sousa, “Globe and Eagle."

- This may have been the year James married Carolene.

1880

- James and his wife, Carolene, known as Clara, lived at 741 Spruce St., but moved to 1723 N. 16th St., where they lived until 1889 or 1890.

- “Pepper opened a New York retail store in 1880, leading to an affiliation with Henry John Distin" (Source: article on "Pepper, J. W.," in The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments).

- "By 1880 Distin was importing instruments for J. W. Pepper of New York and Philadelphia" (Source: Ray Farr, Distin Diaries).

- The New York store was located at 294 Bowery (Source: Musical Times and Band Journal, vol. 6, no. 58, August 1882)

1881

- On March 14, Pepper published Sousa's march, "Guide Right."

- “In 1881 it became necessary, on account of the growth of business, to secure larger quarters, and he removed to 8th and Locust Streets, to a building 22½ ft. by 100 ft., with four floors. At that time he added, as a branch to the business, all kinds of musical instruments, giving particular attention to those used in bands and orchestras.” (Source: 1897 Catalogue).

- According to the August 1881 Band Journal, the move took place on September 15 of that year:

1882

|

| Henry Distin and his son, William, in 1880. (courtesy of Ray Farr) |

- “He soon afterwards added a factory for the manufacture of band instruments, which has grown, during the last fourteen years, to the largest and most complete establishment of its character in the United States” (Source: 1897 Catalogue).

- "Henry John Distin . . . moved from New York to Philadelphia in 1882 and with his son, William Henry Distin, oversaw construction of a factory for Pepper adjoining the existing building" (Source: GDMI article on Pepper; affirmed by Farr, Distin Diaries).

- “J. W. Pepper’s Distin Band Instrument Factory. From April 14th 1882 to May 30th 1883” (Source: “The Progress of Art,” supplement to Musical Times and Band Journal, vol. 7, no. 66, April 1883, as shown below).

- This factory was “in the upper floors of an adjoining building to the store at 8th and Locust” (Source: Letter of Lloyd Farrar to William Ziegel, dated 28 August 1993)

- Howard Earle Pepper, son of James and Carolene, was born on September 11.

- On September 14, Pepper published Sousa's march, "Resumption."

- On December 30, Pepper published Sousa's comic opera, "Desiree," which had a three week run in Philadelphia in 1884.

|

| Image courtesy of the Library of Congress |

1883

- “Opened on June 1st 1883. Everything entirely new. New building, new shops, new lathes, new mandrels, new forges, new machinery. All will be in the large brick building adjoining the present establishment" (Source: “The Progress of Art,” supplement to Musical Times and Band Journal, vol. 7, no. 66, April 1883, as shown below).

- On June 8, Pepper published five more marches by Sousa: “Bonnie Annie Laurie,” “Mother Goose,” “Pet of the Petticoats,” “Right-Left,” and “Transit of Venus".

- "Henry Distin's name was involved in violent controversies in 1883 between the principals in Philadelphia and Conn over the quality of imported versus locally made brass instruments bearing the Distin name; at this time the famous English cornet player Jules Levy, long an avowed Distin supporter, switched allegiance to Conn" (Source: Farr, Distin Diaries).

- Pepper weighed in on this controversy: "It having been asserted that Henry Distin does not make his superior band instruments in Philadelphia; . . . that statements made by us are untrue and misleading, &c. This jealous attack, inspired by an unsuccessful business rivalry, can do us no harm . . ." He then offered a huge reward ($1,000 in gold, plus travel expenses) to anyone who could prove him wrong (Source: Musical Courier).

- At that time, Conn filed a lawsuit over comments Pepper made about Conn's facilities (shown below): "James W. Pepper, manufacturer of musical instruments at Eighth and Locust streets, was arrested this afternoon upon the charge of libel preferred by Charles G. Conn, also a manufacturer of musical instruments at Elkhart, Ind. Pepper publishes a paper in which, it is alleged, on August 1, he made an attack on Conn, charging him with being an imposter and guilty of false pretenses." Ironically, Pepper "was held in $1,000 bail to answer at court"! (Source: The Musical Courier, August 22, 1883, p. 118).

1886

- "By 1880 [Henry] Distin was importing instruments for J. W. Pepper of New York and Philadelphia, and in the summer of 1882 he moved to Philadelephia to help Pepper establish a factory. Pepper however, wished to sell cheaply to a mass market, so Distin, whose interest was in high-quality instruments, formed a partnership with Senator Luther R. Keefer and other businessmen to establish the Henry Distin Manufacturing Co. (2nd March 1886)" (Source: Farr, Distin Diaries).

- “A Chicago outlet opened in 1886, about the time the Pepper-Distin relationship ended” (Source: GDMI article on Pepper).

1890

- Entirely new building built at SW corner of 8th and Locust, referred to as “The Largest House in the World devoted exclusively to the Band and Orchestra Business” (Source: Print of building used in catalogues, see below).

- “In order to secure needed space for the increasing business, it became necessary, at the beginning of 1890, to purchase an adjoining building, and this, together with the corner property, was torn down and the building illustrated on this page erected [see below]. As noted, this building contains, with basement (in which all of the heavy newspaper and lithograph presses are located) seven floors, each of which is 45 ft. by 100 ft., and is the most complete establishment of its character in this country” (Source: 1897 Catalogue).

- For more about this building, click here.

1891

- James and his family lived at 1400 N. 16th St.

- Sousa talked with Pepper about having him build a modified helicon bass for use in his band.

- On October 10, Pepper published Sousa's march, “The Triton." Pepper hadn't published anything by Sousa for the past 9 years.

1893

- James and his family now lived at 1538 N. Broad St.

- On May 24, Pepper published Sousa's march, “Esprit de Corps” (originally written in 1878, but the band publication didn’t come out until 1893).

- Pepper won an award for his band instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (Source: The Music Trade Review, Sept. 30, 1893, p. 1).

|

| Image courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania |

- This only fueled the rivalry between Pepper and Conn, whose booths at the Fair were right across from each other (see below, bottom middle). Conn, who had also won an award for his instruments, claimed that "the quality of [Pepper's] horns are consistent with the price, which is or course the lowest" (Source: C. G. Conn's Truth, October 1893, p. 9).

1894

- Pepper began leasing warerooms at 1004 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, from which to do his retail business (Source: The Music Trade Review, January 6, 1894, p. 12).

- Conn continued to rant about the award Pepper received at the World's Columbian Exposition for his band instruments, claiming that the award was written by Pepper himself and not approved! Further, Conn accused Pepper of publishing "bogus testimonials" for his instruments (Source: C. G. Conn's Truth, June 1894, pp. 9. 17; see also September 1894, p. 17, "Pepper's Pernicious Pranks").

1895

- Following up on a request from Sousa back in 1892, Pepper built the first Sousaphone:

- For more about this historic instrument, click here and here.

- On April 3, Pepper published his eleventh and final Sousa march, “Right Forward” (which was performed originally in 1881, but the band publication didn’t come out until 1895).

- There was a small fire at the J. W. Pepper building at 147-51 Wabash Avenue, Chicago, causing $1,500 worth of damage (Source: The Music Trade Review, Dec. 21, 1895, p. 1)

1896

- Pepper's Sousaphone went on tour with the Sousa Band early this year (shown below on March 7, 1896, in Salt Lake City, directly behind and above the first chair clarinetist).

|

| Image courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers |

- The Conn vs. Pepper feud continued, this time over claims made as to whose euphonium had been played by Signor Raffayolo, who had recently passed away. But Conn also continued to complain about Pepper's award at the World's Fair, and how he was obtaining testimonials for his instruments (Source: C. G. Conn's Truth, January 1896, p. 11).

- Side windows were broken at Pepper’s music store at 8th and Locust in late May or early June (Source: The Music Trade Review, June 6, p. 11).

- Pepper re-published the band arrangement of Sousa's march, “Transit of Venus,” and piano arrangements were made of both that march and Sousa’s “Triton.”

|

| Image courtesy of the Library of Congress |

1897

- Early in the year, Pepper published piano versions of four Sousa marches, “Pet of the Petticoats,” “Bonnie Annie Laurie,” “Mother Goose,” and “Right-Left.”

|

| Image courtesy of the Library of Congress |

- The Chicago branch was discontinued after May 1, 1897 (Source: The Music Trade Review, March 13, 1897, p. 18).

- “J. W. Pepper, musical instrument maker and importer, of Eighth and Locust streets, Philadelphia, is completing a magnificent department house called The Frontenac at Broad and Oxford streets, that city” (Source: The Music Trade Review, Sept. 11, 1897, p. 19). This was a high-end apartment house, complete with a "Superb French Restaurant," where the Pepper family ended up living (records have them there by 1901). Here is an ad for it in The Times (Phiadelphia) on Aug. 29, 1897:

1898

1899

- Pepper was presented a medal by members of Sousa's Band to recognize his band instruments (this may have been awarded in 1897; in early 1898, Sousa was given all-new silver-plated instruments built by competitor C. G. Conn, including Conn's version of the Sousaphone, which Sousa stayed with from that point on).

1899

- “J. W. Pepper, the well-known music publisher and manufacturer of musical instruments, Philadelphia, Pa., is the patentee of a metal folding bed that embraces superior points of merit. A leading furniture paper says, ‘We are obliged to admit the patentee has one of the finest folding beds yet devised’” (Source: The Music Trade Review, Oct. 28, 1899, p. 25; patent can be viewed online here and here).

1901

- James' wife, Carolene, or Clara, died on April 4, after accidentally stepping in front of a freight train while crossing the tracks after a passenger train had just passed her. Her umbrella obstructed her view, and the sound of the passenger train kept her from hearing the approaching freight train. Here's the headline in The Times (Philadelphia), on April 5:

- James was received as a new member of the Music Publishers Association of the United States at their Seventh Annual Meeting in NY (Source: The Music Trade Review, June 15, 1901, p. 27).

- He filed a patent for his Portable Drum Rack (approved in 1903; patent can be viewed online here).

1904

1906

- James' son, Howard, graduated from the Wharton School at the Univ. of Pennsylvania.

- Howard married Emma May Hillborn (1883-1944) on February 9 in Philadelphia.

1905

- Pepper begins importing and selling Sousaphones, but only briefly. It appears that he never built another Sousaphone after the prototype in 1895.

- Pepper filed a patent for his Bass Drum and Cymbal Holder and Beater (mentioned in The Music Trade Review, Aug. 4, 1906, p. 40; patent can be viewed online here).

1907

- Pepper served as one of the directors of the newly incorporated Excelsior Drum Works company of Camden, NJ (Source: The Music Trade Review, Oct. 5, 1907, p. 27).

1909

- The Pepper company relocated to 33rd and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia (this building still stands today as part of the Univ. of Penn - see below).

1910

- “The manufacture of Pepper instruments continued until J. W. Pepper & Son was formed in 1910, after which most instruments sold by the firm were imported” (Source: GDMI article on Pepper).

- James is listed as living in his apartment building, The Frontenac, on N. Broad and Oxford streets.

1912

- James is listed as residing at 1929 N. 18th Street.

- The Excelsior Drum Works changed its name to the Charles S. Caffrey Co. J. W. Pepper was President, and H. E. Pepper was secretary of the company (Source: The Music Trade Review, Aug. 26, 1916, p. 59).

1918

- Jame's son, Howard, registered for the draft, listing his present occupation as "Mfg auto truck bodies, Chas S. Caffrey Co, Camden, NJ, also owner of J. W. Pepper & Son, 33rd & Walnut St. Phila. Pres. Standard Laboratories Co., 33rd & Chancellor St. Phila."

- Musical Times ceased publication around this time. The last known edition is volume 30, number 325, in which it mentions the challenges created by World War I:

1919

- “Philadelphia, Pa., July 29. – James W. Pepper, head of J. W. Pepper & Son, manufacturers of musical instruments and music publishers, died last night. He was sixty-six years old. Mr. Pepper died in the National Stomach Hospital. His home was at 4532 North Broad street [an empty lot today], where he lived with his sister, Mrs. Clara P. McCulley. Besides his sister, he is survived by a son, Howard E. Pepper, who was associated with him in business” (Source: The Music Trade Review, Aug. 2, 1919, p. 20).

- Cause of death was pneumonia, while being treated for purulent cystitis.

- He was buried at the Laurel Hill Cemetery on July 31 (see gravestone above).

1927

- “J. W. Pepper & Son, one of the old Philadelphia music publishing firms, has moved into its new home at 5014 Sansom street, that city. The Pepper Co. was established in 1876 by J. W. Pepper. At present his son, Howard E. Pepper, heads the company. The Pepper catalog contains many band and orchestra publications, school music and other standard teaching material” (Source: The Music Trade Review, Jan. 15, 1927, p. 41).

1930

- Howard E. Pepper died at age 48 and his widow, Emma May, succeeded him (Source: GDMI article on Pepper).

1941

- The company went bankrupt in 1941 and was sold in 1942 to Harold W. Burtch and a group of other investors (Source: GDMI article on Pepper).

1963

- Harold W. Burtch died; his son, Dean C. Burtch succeeded him as president of the company (Source: GDMI article on Pepper).

1973

- The company moved to Valley Forge.

1984

- The company moved to Paoli.

2013

- The company moved to Exton.

[All images, unless otherwise noted, are either public domain or courtesy of the J. W. Pepper company]