The September 1, 1906 edition of the New York Tribune

Having recently been given a Conn tuba built in 1899, with both "Elkhart" and "New York" engraved on the bell, I decided to see what I could learn about the years when Conn had a branch store in New York City. I first became aware of this period a few years ago, when I read Margaret Downie Banks' 1994 work, Elkhart's Brass Roots, where she revealed that Conn

put his efforts into establishing a retail store in New York City (October 1897) for the sale of his Wonder line of instruments, as well as his inventory of fine violins. Instruments sold at this outlet bore both the Elkhart and New York designations [on the bell] for about eight years. However, following a relocation of the store in 1905, this practice was discontinued (pp. 2-3).

That explained where my tuba was originally purchased, 123 years ago! But I was eager to learn more about Conn's New York establishment, and found that the digital library of

The Music Trade Review provided lots of help.

1897-1899: 23 East Fourteenth Street

Here's the earliest mention I could find, from the July 10, 1897 edition:

It appears that this new eastern headquarters opened the first week of November, "without any set ceremonies or formalities," according to the November 6, 1897 edition:

This "new emporium," which was managed by C. S. Palmer, who had been with Conn for 20 years, quickly became "the Mecca for all musical pilgrims to the Greater New York," as the December 11, 1897 edition declared. That edition also provided a detailed description of the warerooms, which included, in the front window at that time, "a

monster brass Helicon with a forty inch bell and weighing sixty-three pounds." This huge horn served to attract the attention of Christmas shoppers!

The following Spring the warerooms were declared "a model of judicious arrangement and good taste," and it was revealed that Palmer was assisted by W. Paris Chambers, "the famous Conn cornet soloist, also well-known as a talented composer, and bandmaster" (April 2, 1898 edition).

(Photo from the March 23, 1901 edition)

That same edition also provided the following photos of Conn's new establishment at 23 East Fourteenth street:

Exterior of the Conn building with the large display window

One of the display cases inside the building

C. G. Conn's private office area (Conn is standing on the left, leaning against the desk)

By early September, it was reported that "The members of Sousa's great concert band have been frequent visitors equipping themselves with instruments for their fall tour, upon which they left this week" (September 10, 1898 edition). Traveling with the band at that time was

Conn's first Sousaphone.

And, according to the November 12, 1898 edition, the success of Conn's New York branch brought to an end his business in Worcester, MA, near Boston, which had been established over a decade earlier (late 1886):

After a full year of business that was described as both "brisk" and "tremendous," the December 10, 1898 edition playfully noted that the ongoing success of Conn hadn't gone to his head:

While Conn toyed with the idea of adding a small factory above the present warerooms, he instead moved his burgeoning business to a new location, just down the street, the following June (reported in the June 10, 1899 edition):

1899-1902: 34 East Fourteenth Street

Now there was lots of room to expand - all the way up to five stories, in what the October 14, 1899 edition referred to as "Conn's Musical Palace"!

And here is one of the instrument cases inside the new facility, featuring Conn's outstanding tubas where they could be examined more closely:

At this point in his career, Conn was riding high, as noted in that same edition:

But The Review had already celebrated Conn's success four months earlier, by placing him on the cover of the June 3, 1899 edition:

The following year, it was reported that "The members of Sousa's Band, since their return from Europe, are showing in many ways their appreciation of Conn merit and enterprise. The Conn warerooms have practically become their rendezvous. Their visits at the Fourteenth street establishment are frequent" (September 22, 1900 edition).

Three months later, Chambers took on a greater role as Conn's representative in New York City (replacing Palmer?), as reported in the December 15, 1900 edition:

But this relationship only lasted fifteen months. In the March 8, 1902 edition, Conn briefly explained that "The agency for the sale of the 'Wonder,' Conn-queror and American model instruments at 34 East Fourteenth street, New York City, has been discontinued."

And then Conn gave his reason: "I have concentrated my business interests at Elkhart, Ind., where the needs of my patrons will receive personal supervision. All correspondence and orders should in future be addressed to me at Elkhart, Ind., where they will receive the most careful and prompt attention."

Conn continued to advertise in The Review, but now he directed them to Elkhart, rather than his New York warerooms, which were no more. Here's one example, from the September 17, 1904 edition:

But by mid-1905, after a three-year hiatus, Conn was ready to revive his New York Branch.

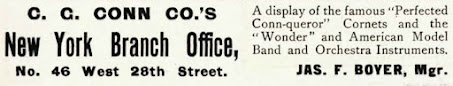

1905-1909: 46 West 28th Street

Note the typo, 48, in the notice above; it was in fact 46 West 28th street, as confirmed by all subsequent notices, such as this one, from the November 25, 1905 edition:

Boyer, who eventually became Conn's "right-hand man," and helped lead the company after Conn retired, was both a gifted musician and a savvy businessman, as reported years later, in the January 8, 1927 edition of the Presto-Times:

And this portrait was included alongside that article:

Boyer's impact on Conn's revived New York Branch was almost immediate, as noted in the December 30, 1905 edition of The Review:

Two months later, Boyer did indeed expand his present quarters, as revealed in the February 10, 1906 edition:

The success of the establishment continued through 1909, leading Boyer to move to a larger and better location at the beginning of 1910 (as revealed in the May 28 edition, seen below).

1910-1912?: 48 West 34th Street

This prepared the branch for continued growth, as explained in the May 10, 1910 edition:

But on May 22, 1910, the Conn factory in Elkhart was

destroyed by fire, and this brought about a role change for Boyer once the factory was rebuilt (and it was rebuilt remarkably quickly, by the end of the year). Here's the notice on the change in the October 29, 1910 edition:

Conn's New York Branch, under Boyer's management, continued through at least the beginning of 1911, as noted in this December 31, 1910 report on Boyer returning to NYC to see the Sousa Band off on its world tour:

However, the last reference to this establishment I could find was in the October 26, 1912 edition. You'll note that Boyer was still connected with it, although not as manager, and it was still understood to be the "Eastern representatives for Conn instruments":

How long this business continued beyond 1912 is not known at present. But the Conn company in Elkhart, of course, continued for decades, well after Conn himself sold the company and retired in 1915. Boyer helped lead it until his death in 1934.

.JPG)

.JPG)

%202.jpg)

%202.jpg)

%202.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)